The 2023-24 Budget has not just maintained but increased the government’s focus on capital spending. This, the government says, will boost India’s long-term growth potential. The time horizon the government has chosen is until 2047, when India will complete 100 years of independence. Given the fact that the current National Democratic Alliance has been in office since 2014, one can evaluate its future economic promises in light of the economic performance of the last eight years. Here are five charts that make this comparison.

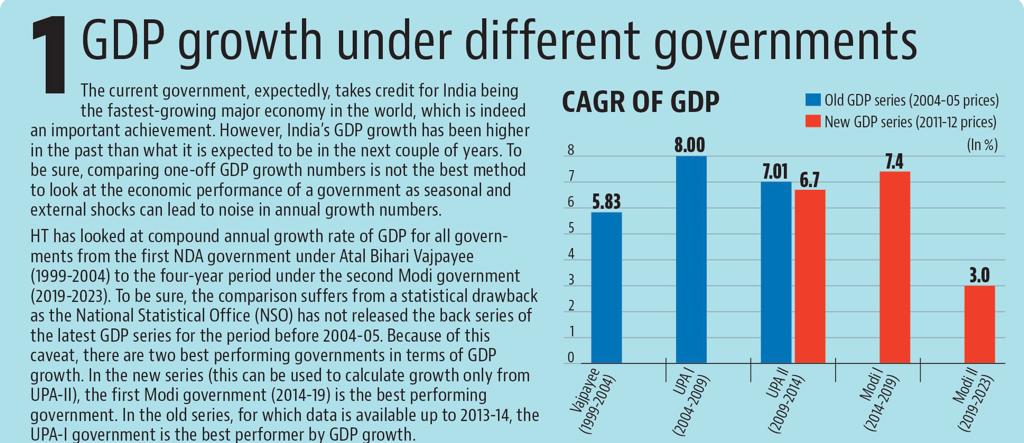

GDP growth under different governments

The current government, expectedly, takes credit for India being the fastest-growing major economy in the world, which is indeed an important achievement. However, India’s GDP growth has been higher in the past than what it is expected to be in the next couple of years. To be sure, comparing one-off GDP growth numbers is not the best method to look at the economic performance of a government as seasonal and external shocks can lead to noise in annual growth numbers.

HT has looked at compound annual growth rate of GDP for all governments from the first NDA government under Atal Bihari Vajpayee (1999-2004) to the four-year period under the second Modi government (2019-2023). To be sure, the comparison suffers from a statistical drawback as the National Statistical Office (NSO) has not released the back series of the latest GDP series for the period before 2004-05. Because of this caveat, there are two best performing governments in terms of GDP growth. In the new series (this can be used to calculate growth only from UPA-II), the first Modi government (2014-19) is the best performing government. In the old series, for which data is available up to 2013-14, the UPA-I government is the best performer by GDP growth.

year period under the second Modi government (2019-2023)." />

year period under the second Modi government (2019-2023)." />

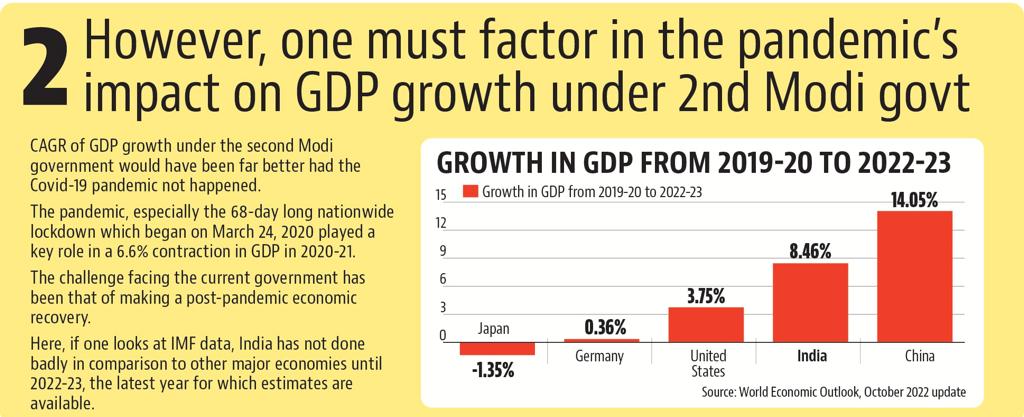

However, one must factor in the pandemic’s impact on GDP growth under second Modi government

CAGR of GDP growth under the second Modi government would have been far better had the Covid-19 pandemic not happened. The pandemic, especially the 68-day long nationwide lockdown which began on March 24, 2020 played a key role in a 6.6% contraction in GDP in 2020-21. The challenge facing the current government has been that of making a post-pandemic economic recovery. Here, if one looks at IMF data, India has not done badly in comparison to other major economies until 2022-23, the latest year for which estimates are available.

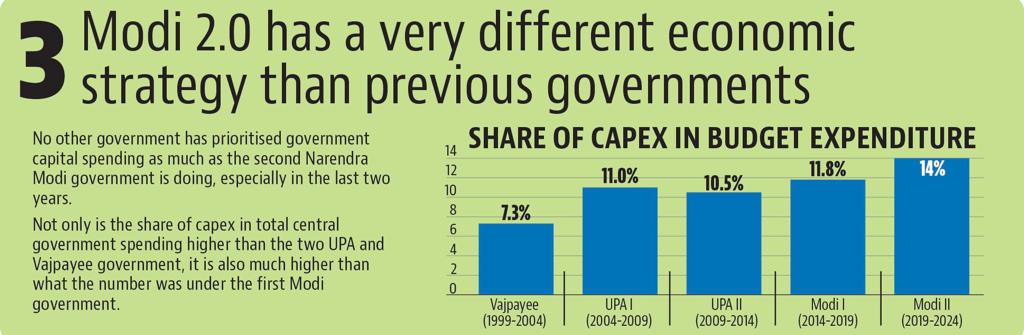

Modi 2.0 has a very different economic strategy than previous governments

No other government has prioritised government capital spending as much as the second Narendra Modi government is doing, especially in the last two years. Not only is the share of capex in total central government spending higher than the two UPA and Vajpayee government, it is also much higher than what the number was under the first Modi government.

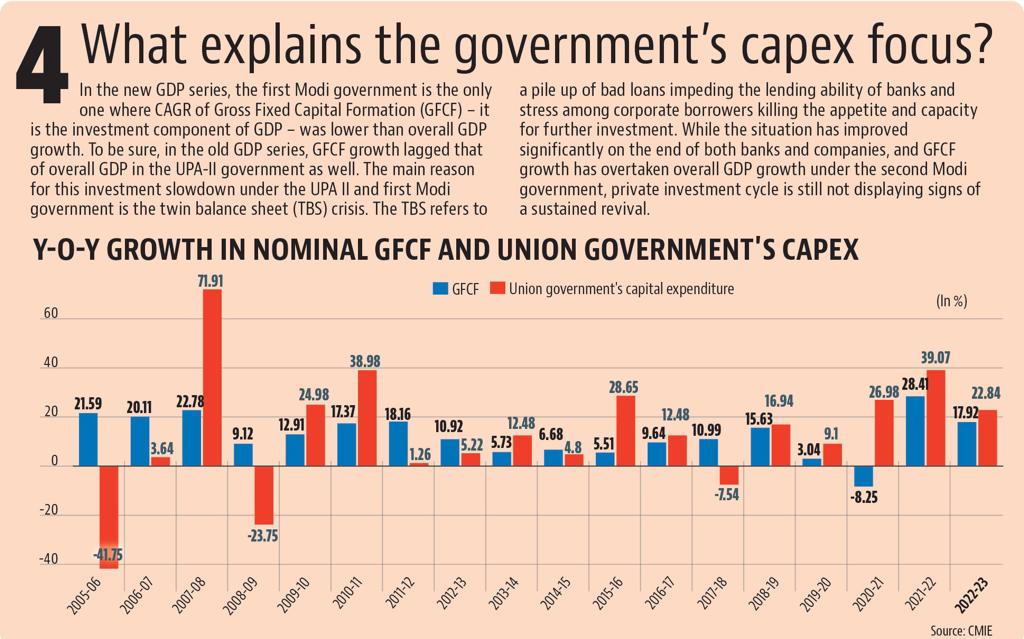

What explains the capex focus of the government?

In the new GDP series, the first Modi government is the only one where CAGR of Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) – it is the investment component of GDP – was lower than overall GDP growth. To be sure, in the old GDP series, GFCF growth lagged that of overall GDP in the UPA-II government as well. The main reason for this investment slowdown under the UPA II and first Modi government is the twin balance sheet (TBS) crisis. The TBS refers to a pile up of bad loans impeding the lending ability of banks and stress among corporate borrowers killing the appetite and capacity for further investment. While the situation has improved significantly on the end of both banks and companies, and GFCF growth has overtaken overall GDP growth under the second Modi government, private investment cycle is still not displaying signs of a sustained revival.

But private investment revival also needs an optimistic demand outlook

The government’s capex boost being synced with an easing of bank and corporate balance sheets is hoping to start a virtuous cycle of public and private investment. However, it is important to underline that the key driver of private investment is expectation of future demand in the economy. RBI’s latest Industrial Outlook Survey shows that the net share of businesses who believe that their current production capacity is more than adequate to tend to future demand has been increasing in the past few rounds. This is perhaps the most important explanation for private investment not gaining momentum. Unless this changes, the virtuous cycle government is hoping for will not materialise.